A Longing for Fire and Sunlight

The Southeast’s Vanishing Grasslands

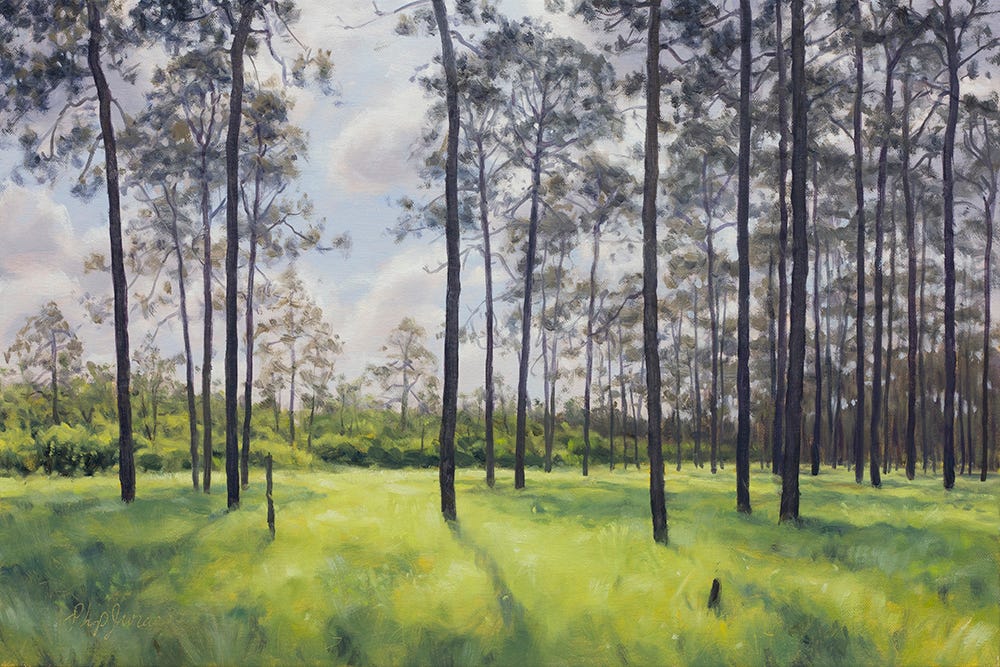

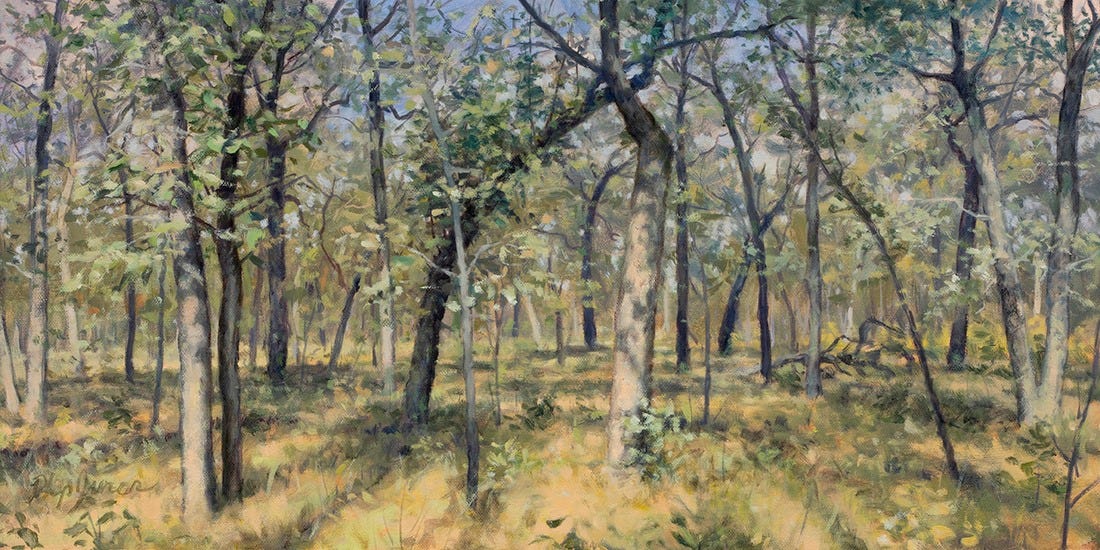

This feature from our Fall 2024 issue offers a glimpse of the Southeast’s vanishing grasslands through Tom Poland’s words and Georgia artist Philip Juras’ paintings. At the end of this story, view a new painting by Juras that offers a rare glimpse of what was once a prairie in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, followed by his reflections on what inspired him to paint this particular piece.

Free subscribers can read a preview. Consider upgrading the read the full story.

A Longing for Fire and Sunlight

Story by Tom Poland • Paintings by Philip Juras

Imagine an unsullied Southland with vast tracts of sun-filled, grassy woodlands, open glades, and even the occasional prairie sweeping from horizon to horizon. Accustomed as we are to shady forests, farm fields, and urban sprawl, that's not an easy thing to do. Native grasslands once existed in the Southeast, yet, like other natural systems, humans destroyed them out of necessity and ignorance. But those folks might have been a bit less voracious if they had better understood nature.

The next time aloft over the Southeast, note the crazy quilt below of croplands, forests, fields, and pastures. You’ll see towns and cities connected by linear deserts we call highways. You’ll see black wastelands we call parking lots. Grasslands’ demise began when European settlers stepped ashore with their fire suppression ways, axes, and plows. Manifest Destiny and something called progress began to bite, chew, then gobble native grasslands. The appetite was insatiable and today native grasslands are a ghost of what they once were. Think of them as remnants. Until the colonists set foot here, however, flower-filled grasslands had long staged a show. Witness this majesty through the eyes of another.

“It would be difficult to imagine anything more beautiful,” Tennessee settler Reuben Ross wrote in 1812 of the once vast Pennyroyal Plain Prairie of southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee. “Far as the eye could reach, they seemed one vast deep-green meadow, adorned with countless numbers of bright flowers springing up in all directions.” YaleEnvironment360 published that passage in “Forgotten Landscapes: Bringing Back the Rich Grasslands of the Southeast.”

YaleEnvironment360 again: “At a fine scale (less than 100 square meters), Southeastern grasslands have some of the highest plant richness in the world. A prime example is North Carolina’s Green Swamp Preserve, home to rare species of conservation concern, like the Venus flytrap and the Grasshopper Sparrow.”

And what kept those grasslands and savannas healthy and intact? Two things you might consider adversaries: fire and herbivores. Fire and grazers share a relationship and American Indians knew this. They burned grasslands knowing fire encouraged new growth, which attracted herbivores such as deer, elk, and bison, and that pleased Indians who saw grasslands as a source of food, fiber, and medicine.

Native Americans and native grasslands made a fine pairing. Indians set grasslands afire when infrequent lightning did not. Grasslands began shrinking as shady forests emerged, and agriculture and much later urban sprawl consumed it.

Friend or Foe?

Eastern red cedars were the only Christmas tree I knew as a boy. (It’s a juniper, not a cedar, if truth be told.) Dad’s saw spat fine bits of wood and an aromatic fragrance perfumed the cool November air. Imagine my dismay to learn that the eastern red cedar has the potential to grow into an enemy of grasslands.

The next time you make a country drive, pay attention to fence lines. Note the cedars along the fence line, planted by seed-eating birds who found a good perch for taking care of business.

The absence of fire creates the perfect environment for eastern red cedars. Like Birnam Wood in Macbeth, the cedars advance. Orion magazine’s August 27, 2024, feature “Protecting the Prairie,” refers to the eastern red cedar as a “scourge of our region’s native prairie ecosystem.” Eastern red cedars are native, but they’re restricted to rock outcrops which are fire resistant and to sunny places as they don’t do well in shade. In the Carolinas cedars are not as big a threat as they are elsewhere, although they’re one of the many trees that shade out grasslands.

In 2024 an eminent landscape artist and I began an email correspondence. Of Philip Juras, it’s said he has “the savvy of a naturalist and the soul of a poet.” When you see a Philip Juras landscape you ache for what was. His remarkable art and words reveal native habitats in a way that’s sublime and transcendent—gloriously consequential.

He understands grasslands and practices what he preaches. For fifteen years Philip has volunteered as a Wildland Firefighter Type 2, or “Ecoburner,” with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and The Nature Conservancy.

And so it was we met late one afternoon to discuss native grasslands and their remnants in the Southeast. We planned to visit an oak savanna that happened to be just off the route I take to my Georgia homeland. Eager to see it, I almost found it on an August Sunday. The air was heavy and still. Muggy. After a considerable hike I mistook a new forest service road to left as the path to take. It wasn’t but I found myself standing before the strangely beautiful rattlesnake master, a vestige of grasslands destroyed by changing land use and fire suppression.

And how did rattlesnake master, a plant of the prairie, get its name? Native Americans used it as preventive medicine when handling rattlesnakes in ceremonies. It did not help if you’re bitten, as settlers learned to their dismay.

More grassland loss occurred thanks to the Great Wagon Road. Settlers migrating south found the largely treeless landscapes accessible, easier to settle, and easier to convert to fields and range lands. And settlers could better spot hostile Indians who were right to be more than a bit riled up. Settlers’ plows disrupted soil, destroyed grass species’ deep root systems, and disrupted the bacteria, fungi, and animals that make soil fertile. And then their fear of fire added to grasslands’ misery. Over ninety percent of Southern grasslands declined from their former distribution. It would be my good fortune to see a survivor.

Walking Through a Savanna With Philip Juras

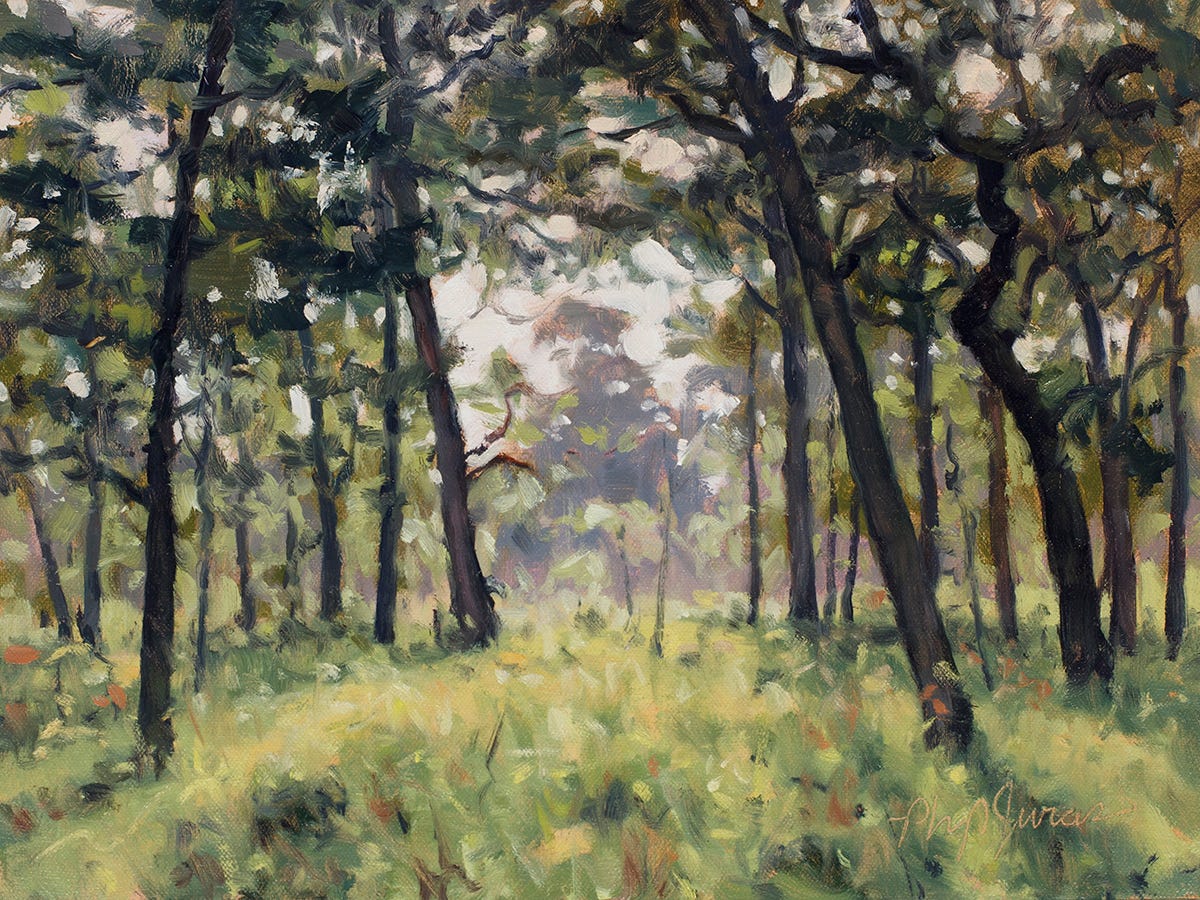

August 21, 6:15 p.m. Philip Juras and I are walking through an oak savanna. We’re seeking a rare place, a place I hope, where the whip-poor-will calls come sundown. Philip shows me where I made a wrong turn two weeks earlier, and we make our way to the oak savanna.

When colonists arrived, they suppressed fire and took plow and axe to the land. Their cattle’s grazing did somewhat what buffalo had done: keep out invasive plants. In a blessing, the plows and axes missed a place here and there … a rare here and there …. A place where we walk.

“A botanist,” said Philip, “would take forever walking through here. So many plants to see. A few post oaks here could predate settlements.” The post oaks were large and the sunny spaces between their canopies let grasses flourish, but so can invasive trees. Lightning strikes and American Indians burned grasslands across the South, ridding them of fire-intolerant shade trees like maples and poplars. In Florida and much of the coastal plain lightning alone was frequent enough to keep grasslands open.

My field khakis sport stripes of soot. Soot, dead tree seedlings, and charred wood speak, “A U.S. Forest Service prescribed burn passed through here.”

We slog through brush and briars to an open area and go our separate ways. Light sparkles upon leaves and the tips of blades of grass. I photograph trees and grasses in gold light. Very fortunate, these survivors.

Some thirty minutes later I see Philip painting. I make my way to him. I hesitate to talk to break the spell but I do. “Something special’s going on here,” he says.

I knew to be quiet.

I watched Philip watch the light. It moved fast and angles changed as the sun dropped.

I sat at the base of a post oak and used my camera bag as a desk. I make notes. “We’re in the middle of nowhere. Nothing but light, trees, and remnant prairie. And two UGA guys in a South Carolina forest. It’s quiet. Then, from the northeast, a whisper becomes a roar. An airliner. Other than that, there’s no sign of civilization. No traffic. It’s so quiet I half expect to hear bison thunder through. This savanna. It’s evocative of what was. You will never lay eyes on it except as you do here, thanks to Philip’s vision.

Philip backs away five yards. He looks at his painting. I do too. The savanna materializes right before my eyes. He resumes. His brushwork is swift yet delicate. His brush’s handle reflects a glint of dying light.

All is quiet again. The airliner took its roar west over the horizon. I hear cricket chitter, wind in treetops, and birdsong. I ease up to the easel. Philip’s painting is as one with the savanna. Remove its frame and it blends right into the scene.

He glances at the western light as if it will die any second now. His brush makes soft thumps. He leans in and touches color. Deft strokes as his eyes continually gauge light, color, dimension, and intangibles known only to the artist. I watch as he signs his name to a most special painting.